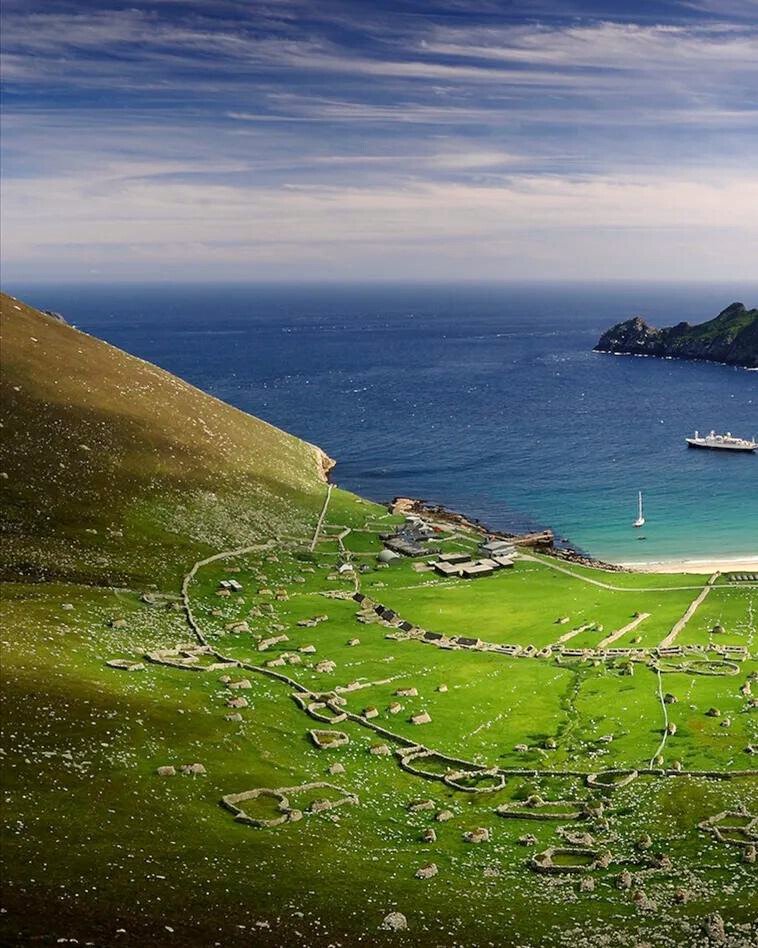

St Kilda, a remote and rugged archipelago in the North Atlantic, consists of four primary islands: Hirta, Dùn, Soay, and Boreray. The largest of these, Hirta, is famous for its towering sea cliffs, the highest in the United Kingdom, soaring majestically above the surrounding waters. While the smaller islands were historically used for grazing sheep and seabird hunting, Hirta was the archipelago’s heart, supporting human life for over two millennia. However, this once-thriving community was completely abandoned in 1930, transforming the village into a haunting ghost town, now left to the mercy of time and the elements.

The history of Hirta is one of remarkable resilience and adaptation. Its inhabitants lived in isolation for at least 2,000 years, relying on the harsh environment and the resources the islands could provide. The community was closely knit, bound together by shared traditions, language, and a deep connection to the land and sea. Small boats, essential for travel between the islands, enabled the residents to fish, hunt seabirds, and trade with occasional visitors from the mainland. Life was simple but demanding; the islanders were expert farmers and fishers, raising livestock like the unique Soay sheep and cultivating small plots of land to grow barley and potatoes.

The islanders lived in traditional stone houses well-suited to the harsh weather conditions that often lashed the archipelago. Despite the isolation, the people of Hirta maintained a vibrant community life. They held regular gatherings, shared communal tasks, and celebrated festivals passed down through generations. Their language, culture, and way of life were unique, reflecting their long history of isolation from the mainland.

However, by the early 20th century, the forces of change began to erode the traditional way of life on Hirta. The outside world started encroaching on the islanders’ lives, bringing new challenges and opportunities that would eventually lead to the community’s decline. The outbreak of World War I had a devastating impact on Hirta. Many of the island’s young men left to fight in the war, and the experience often changed those who returned. The loss of these men, combined with the psychological toll on those who survived, left the community weakened and vulnerable.

The war also brought new diseases to Hirta, which spread rapidly among the population, further decimating the community. The island’s isolation, once its greatest strength, became a liability as the residents struggled to cope with the increasing demands of modern life. Medical care, which had always been limited, became a critical issue as more people fell ill and the small community found it increasingly difficult to sustain itself.

By the 1920s, the population of Hirta had dwindled to just a few dozen people. The traditional economy, based on farming, fishing, and seabird hunting, was no longer viable. Many younger islanders had already left, searching for better opportunities on the mainland or abroad, leaving behind an aging and increasingly infirm population. The remaining residents found it harder to maintain their homes, tend to their livestock, and perform the daily tasks necessary for survival.

In 1930, recognizing that they could no longer sustain their way of life, the last 36 residents of Hirta made the difficult decision to request evacuation to the mainland. They left behind their homes, land, and ancestors’ graves, ending over two millennia of continuous habitation on the island. The evacuation marked the end of an era, as the village of Hirta was left to the elements, becoming a ghost town almost overnight.

The legacy of Hirta and the wider St Kilda archipelago lives on. In 1986, the islands were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for their cultural significance and unique natural environment. The archipelago is home to globally important seabird colonies, including puffins, fulmars, and gannets, which thrive in the island’s cliffs and rugged terrain. The Soay sheep, one of the rarest breeds in the United Kingdom, also continues to roam the islands, descendants of the livestock once tended by the islanders.

Today, St Kilda is owned and managed by the National Trust for Scotland. It remains a place of extraordinary beauty and historical significance, attracting visitors, historians, and scientists who seek to understand the unique way of life that once flourished there. The abandoned village on Hirta stands as a poignant reminder of a lost world, a testament to the resilience of the people who once called this remote island home, and a symbol of the inevitable changes that time brings.